How can the web be ethical?

The question of web ethics and web activism has long been debated and seeks to question our relationship with technology and, more broadly, with technique and progress. We are going to see how this question can play a part in our thinking as designers and developers.

Chapter 1

The web, a technology like any other?

Like any other technology, the web needs to be considered in terms of its relationship with society and with people. By looking at the history of technology, we can see the emergence of themes that can provide lessons for today’s designers.

The most powerful cause of alienation in the world of today is based on misunderstanding of the machine. The alienation in question is not caused by the machine but by a failure to come to an understanding of the nature and essence of the machine, by the absence of the machine from the world of meanings, and by its omission from the table of values and concepts that are an integral part of culture.

Gilbert Simondon, On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects, 1958

Rejection of the Industrial Revolution

The question of the relationship between human and technology is as old as technology itself. In the 19th century, for example, the first science fiction novels, particularly William Morris’, expressed a form of concern and rejection of the development of technology and the process begun by the Industrial Revolution, a rejection that was not only aesthetic but also, and above all, political and social.

At the root of Marxism

Marxism was born in the 19th century, and at the heart of Marx’s theses was a reflection on the relationship between the mechanised industrial production process and the alienation of workers and of humans. Marx lived in London for several years in the 1850s, and it was there that he came face to face with the misery caused by industrialisation in England that he began to write The Capital.

The turning point of WWII

While the question of progress and science has always been particularly fertile philosophically, and led to the political and social revolutions of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, World War II, with the development of nuclear weapons, brought the issue of the use of technology and science and the ethics that must accompany it back to the heart of philosophical questioning.

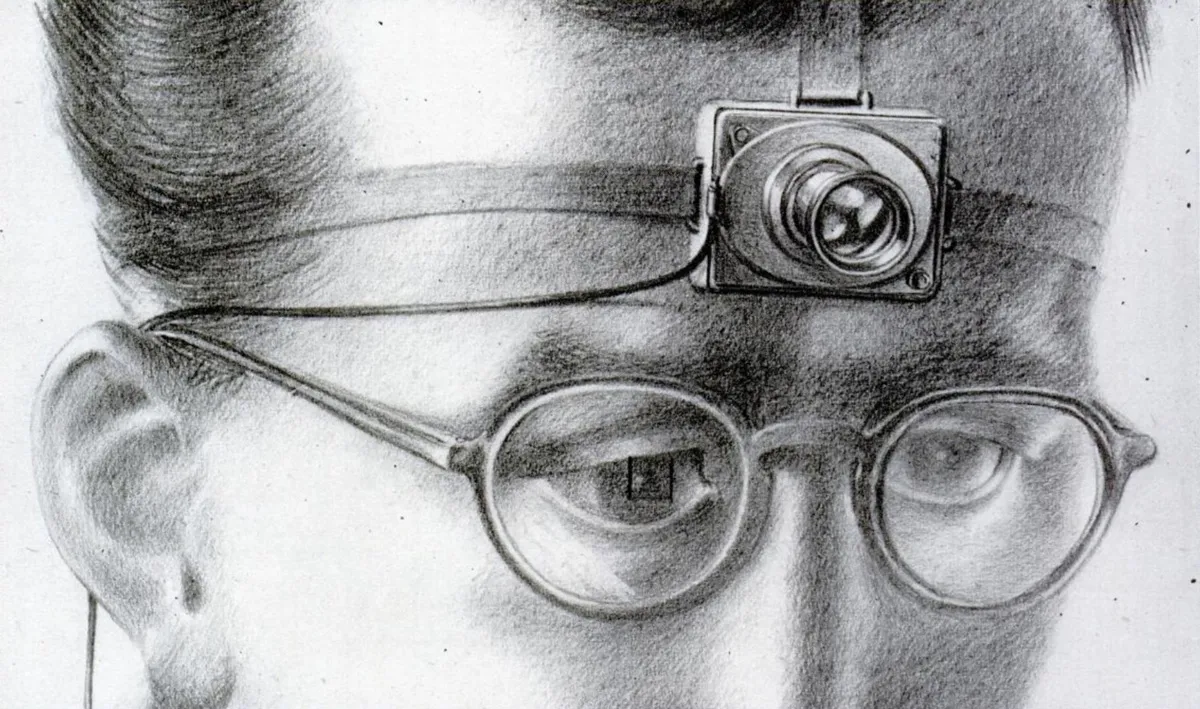

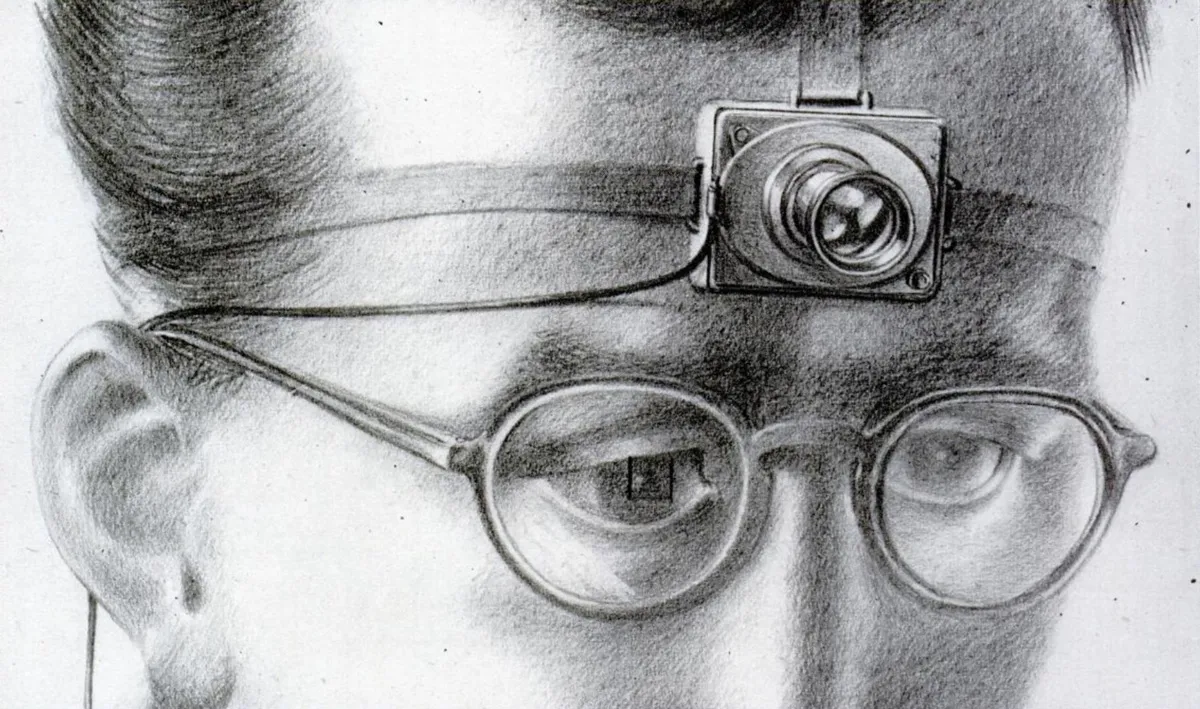

First published in June 1945, then in a new version just after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in September 1945, Vannevar Bush’s text As we may think marked a turning point and was to have a decisive influence on the initial thinking that led to the Internet and the web as we know it today. In this text, the American scientist expresses his concern about the use of science for the sole purpose of destruction, and explains his desire to see the scientific world put all its energy into the development of information technologies for the transmission and accessibility of human knowledge to all.

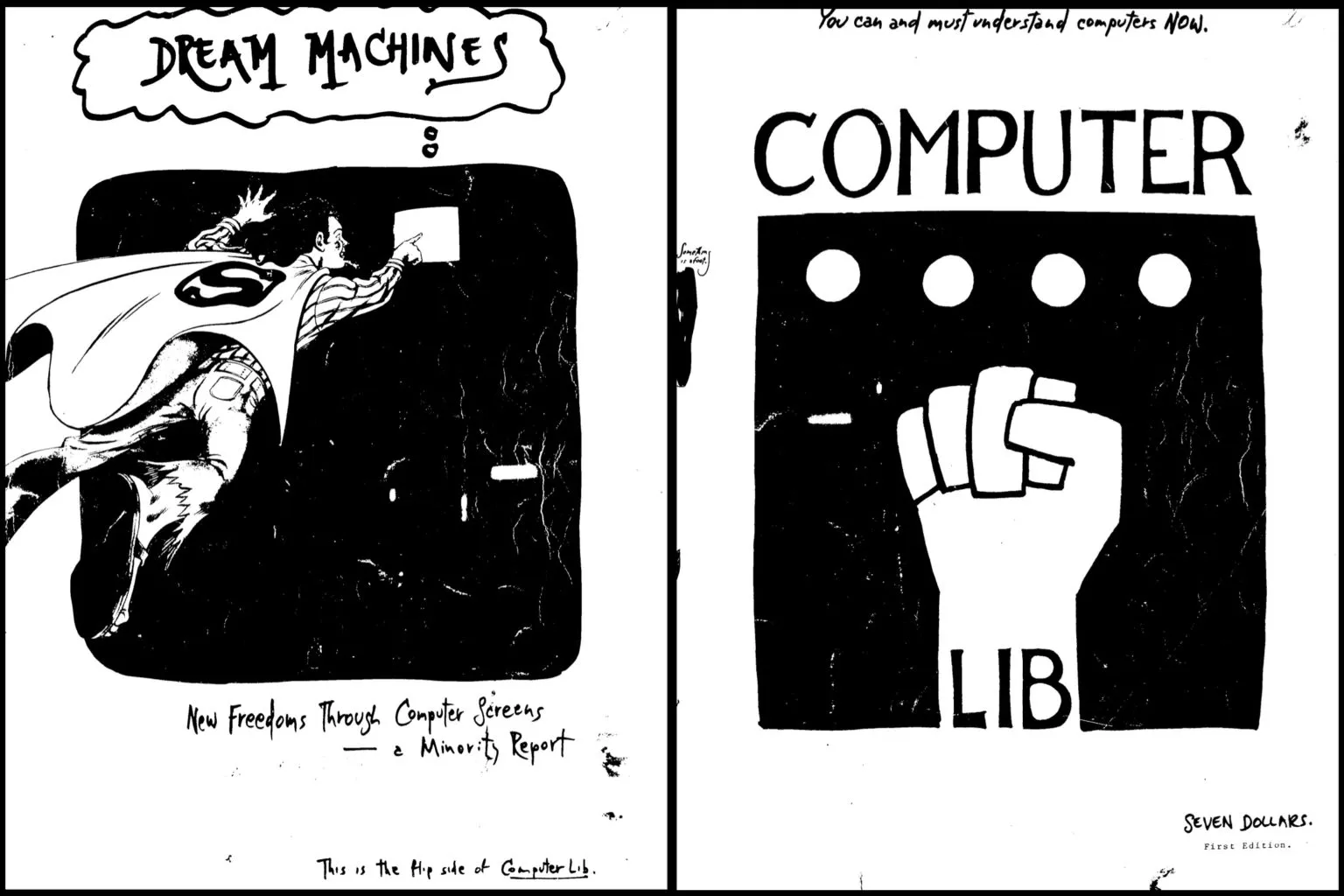

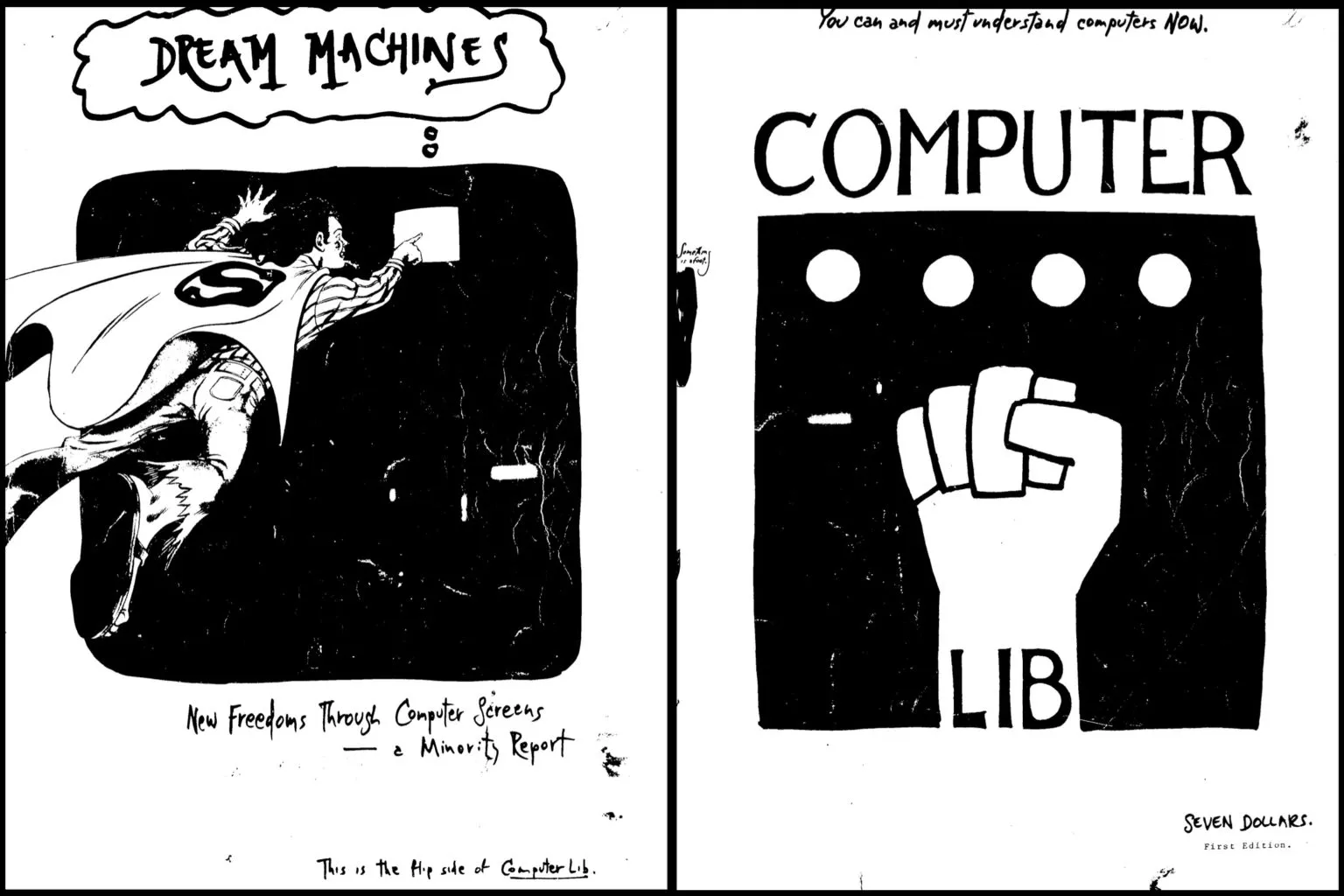

With the development of the Internet from the 1960s onwards, this utopia gradually became a reality, but very soon certain thinkers began to pave the way for a reflection on the issue of alienation from the first computers and on the issue of decentralisation, in opposition to the birth of the first computer giants such as IBM. Ted Nelson, with his book Computer Lib/Dream Machines, was to become the figurehead of a form of computer counter-culture that is still very much alive today.

Chapter 2

The disappearance of the libertarian ideal

Unfortunately, although these ideas emerged from the earliest research into the concept of the internet and the web, they ultimately failed to prevent the development of an extremely centralised web in the hands of a few capitalist giants.

The internet was once a highly decentralized system. In the earliest days, there were no large corporations or service providers like Ashley Madison or Facebook or Twitter, or behemoth databases to house your information. If you wanted to join up, you plugged in a computer and found a connection through a service provider, and that was basically it. You were online. Your computer was a “peer” of the other computers. It was a computocracy.

Paul Ford, Reboot the World, 2016

The end of vernacular web

The open, libertarian spirit of the early years of the web in the heart of the 90s, what Olia Lialina calls the vernacular web period, was followed by a period of exponential development that led to the creation of huge monopolies on the web, starting with Google, and then in the 2000s, the emergence of social networks and Facebook in particular.

The era of Big Data

The libertarian ideal of the early days gave way to the most voracious technocapitalism, which relegated the issue of information sharing to the background. This is the era of Big Data and its worst political abuses, such as the Cambridge Analytica scandal in 2016, and its sociological abuses, which had a decisive impact on the mental health of many individuals.

UX everywhere

Behind these abuses lies a whole industry geared towards maximising profits, which will influence the way we think about the web on a large scale, including in sectors where economic profit is not the main concern. Cookie collection, user tracking and dark patterns are all UX techniques developed within Big Data but which will gradually spread everywhere, forcing designers and developers to take a stand against technologies that are harmful to both society and the environment.

Chapter 3

Rethinking the web on a small scale

Faced with the hegemonic power of GAFAM, both economically and politically, a form of web activism has gradually developed on a small scale among designers, developers and, more broadly, some web users, setting up what Domitille Debret calls “a gentle act of anarchy”. For many of them, it’s not so much a question of overthrowing a system that looks like an insurmountable Goliath, but rather of proposing a disruption, an ethical reflection on the scale of the individual and the community.

I evoke the term handmade web to suggest slowness and smallness as a forms of resistance.

J.R. Carpenter, A Handmade Web, 2015

Open source as an alternative

An important design scene has been created around the issue of open source, particularly in Belgium, around the work of collectives such as Luuse and Open Source Publishing, who are conducting both a political reflection on the role of the designer and the organisation of work, and a technological reflection through the design of open source tools. Their approach is reminiscent of the notion of the handmade web theorised by J.R. Carpenter, which places at the heart of design a relationship of dialogue and understanding between the individual and the technology.

Against alienation

This calls into question a whole approach based on the alienation of users (think of the work of Anja Groten and Hackers and Designers on this subject), but also, more broadly, a conception of the web that seeks to put back at the centre a relationship of trust and awareness with regard to web objects and to erase, if only very partially, the mystery and complexity deliberately and opportunely put in place by the big web companies.

Domitille Debret’s One-tailed project seeks to show the absurdity of collecting browsing data by having a goldfish navigate websites that measure user activity. While the project’s ambition is not so much to falsify data on a grand scale, it does seek to show the humility of the designer’s role and their position as initiator of reflection.

If a website has endless possibilities, and our identities, ideas, and dreams are created and expanded by them, then it’s instrumental that websites progress along with us. It’s especially pressing when forces continue to threaten the web and the internet at large. In an age of information overload and an increasingly commercialized web, artists of all types are the people to help. Artists can think expansively about what a website can be. Each artist should create their own space on the web, for a website is an individual act of collective ambition.

Laurel Schwulst, My website is a shifting house next to a river of knowledge. What could yours be?, 2018

Ethics at the heart of the web of the future?

Nevertheless, the subject of web ethics seems to be gradually taking on more prominence, and even the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) is beginning to reflect on it through the TAG (Technical Architecture Group). Although these ideas are only in draft form at the moment, and the W3C has not yet ventured to validate them, they are a first step towards a more global appropriation of this issue, and not just by activist designers and developers.

w3.org